- Home

- Farideh Goldin

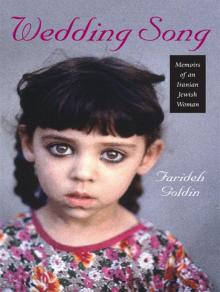

Wedding Song Page 3

Wedding Song Read online

Page 3

In my father’s version, they followed the girl home, and when they were sitting in her house having chai and rice cookies, my father spotted a girl playing with the prospective bride. She had fair skin and wild black curls. “That one,” he whispered to Masood. “That girl is the one I want.”

The day after, they went to this girl’s house with flowers and a box of Gaz, Isfahan’s famous sweet confectionery. My maternal grandmother Touran wouldn’t let them in, fearing they could be thieves, staking the house to steal her belongings. They finally convinced her to take the gifts and to check with a certain person who had given his daughter to a Shirazi and knew my father’s family.

When they came back the day after, not only had Touran checked their credentials, she had also visited her uncle, Dr. Sayed, asking for his advice.

“Give her to them,” he had said.

Maman’s Story

When I was thirteen, the same age as my mother at the time of her marriage, Maman sat down next to me. Her fingers traced circles around the peacocks and pomegranates on the Persian carpet as her eyes watched me. I was stretched out on my stomach, legs crossed and raised behind my back, one arm under my chin, doing my homework, reading the false history of Iranian kings and their conquests. I wished she would go away.

She picked up a book, turned it around, and leafed noisily through the pages. I wanted to tell her that I had an exam the following day, that I didn’t have time to give her attention, that she needed to leave me alone. Instead, I stabbed the words on the paper in an attempt to lodge them in my brain, already too preoccupied to absorb the information. I reached to grab the book. “Maman!” I started to tell her to leave, but it was too late. She was reading a poem in a sing-song way. When she finished, she giggled, a child in front of the class expecting applause.

“I was a good student,” she said.

“Okay.” I rolled over, sat up, and collected my books to leave.

“I was good at everything but math.” A muffled laugh escaped her cracked lips; her irises glimmered with green dots I had never noticed before.

I didn’t respond. I wondered if I should go to a friend’s house to study.

Then my mother told me her wedding story for the first time. “I’d just come back from school,” she said, “sitting down just like you to do my homework.”

My mother’s voice was flat. Her eyes lost their green speckles, their light. She took my pen when she explained how her mother had taken hers and told her not to bother; they had to prepare for her wedding, pack her bag to leave for a new city.

I imagined my maternal grandmother rushing about the house. I remembered her unsmiling face, her rough hands, her hair parted in the middle and severely pulled back. I had seen her two or three times, once during her visit when my brother was born. She and her youngest son, my five-year-old uncle, shared the bedroom with us. My father moved to his mother’s room for a few days. Grandmother Touran avoided the members of our large household and constantly snapped at me and my uncle. She kept away from my paternal grandmother, but when in her presence, called her Khanom-bozorg, great lady. Giving respect and honor to her daughter’s mother-in-law, she hoped to soften her heart toward my mother. The children, even my cousins, adopted the title to address my paternal grandmother.

During her visit, my mother’s mother used the space heater in the room to cook simple meals because she didn’t want to eat with the rest; she didn’t want to be in the way; she didn’t want to impose. Intensely uncomfortable under somebody else’s roof, she couldn’t wait to get back home. She shunned intimacy; there were no hugs and kisses.

On the day of her departure, grandmother Touran shook her index finger at me. “You take care of your mother now.”

I didn’t know why my mother was teary. Touran had sent her only daughter away, telling her abruptly that she would go to a far-away city as the wife of a stranger. My reaction was hardly sympathetic. Maman should have felt lucky for marrying into my father’s family, leaving her own house crowded with little brothers and an angry mother. Baba always told me that my mother had married above her class.

My mother reported her wedding story in a clear and unemotional voice like a documentary video. I wanted it to end so I could get back to my own life. I much preferred tackling the rote memorization of the chapters in my textbook. Nader Shah was a great king. He conquered India, smashed their idols, killed anyone who didn’t convert to Islam, established Farsi as the main spoken language. He brought back to Iran diamonds, rubies, strong slaves, beautiful women.

I had never seen my mother’s childhood home in the cramped ghettos of Hamedan, yet I could envision that house with no running water, a mud stove, and little bodies sitting on their knees by the walls, their mouths open wide crying in hunger or anticipation of food. I pictured my mother as she had described herself. A bucket filled with spring water clanged against her legs and wet her skirt as she headed home along dirt-covered alleyways. Moslem boys blocked her way and dropped horse dung in the water before she turned the corner to her house. Having cleaned other people’s homes all day, her mother stared at the water in disbelief. It was getting dark and there was no water at home to cook for the little ones. Could that have been the point at which my grandmother decided her daughter was useless? Years later, I wondered if my grandmother feared that when she was out, my mother would get raped or kidnapped and converted to Islam. In any case, she was a liability. My maternal grandfather was detached as a husband and a father, so grandmother Touran decided to pass the responsibility of my mother to another man.

My mother approached her father for help. He shook his head but didn’t interfere. She ran away to her aunt’s house, who took her home and chastised Touran. “Don’t do it! Don’t do what our mother did to us.”

“Too late!” Touran had given her word. The contract was sealed.

Maman lowered her head. Her shoulders drooped; she gazed across time, not space as she recollected the events. If I could go back in time, I would hold her tight, put her head on my shoulder, and caress her hair. But being a child myself, I traced the birds on the carpet with my index finger as I learned of my mother’s childhood grief.

“I threw myself on the floor and begged my mother, ‘Maman, Maman, please don’t send me away, please, please.’”

It troubled me that she was using the same word for her mother that I called her. I couldn’t think of her as someone’s child. My feet were asleep. I stretched them in front of me and rubbed them. “Maman, baseh,” I begged her. “Enough!” My legs tingled. I needed to get up and walk, but my mother kept on talking. She had to recreate the event for me. An army of crows covered the backyard, then rose and swirled away. I wished I could fly. Maman wouldn’t stop. Her words held me down.

“I kissed her feet. I told her that I would be her maid. ‘Please don’t send me away. I’ll stay home. I’ll clean. I’ll cook.’”

“Baseh,” I said as if to myself. What did she want me to do? I put down my pen on the carpet and slumped. No point trying to study. The smell of a quince stew filled the house with its sweetness, and made me hungry. I wanted to remind her to go to the kitchen and check on it, but I stayed silent. She had to finish her story. So I listened.

“I will take care of my brothers,” she had pleaded to her mother. “I am your only daughter. I will be your servant. Please don’t let them take me.”

My mother paused. She stared into empty space. Her words sat like stones on my chest. I couldn’t move. I didn’t know why she shared her story with me when there was nothing I could do for her. A small crack opened in her chapped lips, but she went on. “Maman peeled me off and turned her back.”

Sweat covered my back. Suddenly, I understood her point. She could do the same to me. I closed the book.

My mother’s story still burns in my mind. The wound has become more stubborn and painful since I married and became the mother of three daughters myself.

For many years, I was jealous of my friends whose

mothers didn’t burden them with the weight of the past, who went home from school to share their days with their mothers. What could I tell mine? That my geometry teacher was failing me because I didn’t take private lessons with him? That my calligraphy teacher called me a trouble-making Jew? That I argued with a classmate? That I needed winter shoes? I even left out my happier tales of accomplishments and friendships from our brief conversations. Would my mother care to know that I was the best essay writer in my high school? My life was detached from hers. She took no joy in my happiness, and my problems paled in comparison with her trauma. There was nothing to say. I stayed silent in the hope that she would be too.

I learned to become self-sufficient, keeping away from her to save myself. I drowned myself in foreign books whose characters were strange and alien, whose problems were not mine. During the years I lived with her, my mother told her wedding story over and over. With each retelling, I distanced myself further, until I could scarcely bear to be in the same room with her alone. Finally, when I started to cover my ears and run out of the room, yelling, “I know, I know,” she gave up retelling her story.

When I was in my twenties, I could still hear her mumbling it to herself as she sat alone on a low stool plucking chickens, or rubbing the soap into the dirty clothes. She became quiet when I was in my thirties. Instead, she would stare at me. I took her to the theater once when she was visiting me in the States. I chose a musical with beautiful costumes so she wouldn’t need to understand the words. But I couldn’t concentrate on the stage. Her gaze burned my cheeks.

“Stop it,” I reprimanded her. “Don’t stare at me. Look at the stage.”

“What? I wasn’t looking at you,” she lied.

If my kids hadn’t been with me, I would have yelled at her; I would have left the show.

Now I want her to tell me more of her story, but she refuses to talk. For years she feared that I would forget. Now she is afraid that her writer-daughter will record her pain and bring the wrath of the family upon her. And I am torn apart by her words and by her silence.

Baba’s Story

I have always loved my father’s words. I could listen forever to his stories, always fascinating, adventurous.

At age seven, mesmerized by the sound of shopkeepers in the busy downtown, I lost my mother among hundreds of other women wrapped in their chadors, crowded among men hauling bundles of linen and carpets on their backs, young boys carrying trays of tea for their bosses, and tribal girls trailing their mothers, buying kitchenware for their dowries. Disoriented and timid, I didn’t ask for directions, fearing that I would be tricked and kidnapped if the strangers around me knew my mother had left me. A Jewish girl deep in a religious Moslem neighborhood invited misdeeds, my grandmother had always told me. I tried to reverse my steps. Remembering that we had walked toward the minaret of the mosque, I turned my back to it. Finally, I reached my father’s shop to learn that my mother had stopped by earlier to report that I was missing. I didn’t cry, but I wanted to. I bit my lower lip and threw myself in a metal chair, too exhausted to move. My father gave me a cup of tea with a yellow date and then held my hand and walked me home. On the way, he told me about his trip to Bab-e Anar, the village of pomegranates.

Baba at eighteen, still wearing a beard as a sign of mourning for his father’s death.

When he was thirteen years old, Sha’ul the peddler hired him to help with his accounting in the faraway village. My father had never left home before.

Listening to my father’s rendition of his childhood story, the melodic intonation of words mixed with poetry and zarbol-masal, Persian proverbs, I forgot my own misadventure. I felt as if I were with him on the back of an open truck on the only paved road heading south into the mountains; I imagined the old tires kicking off dust. Together, we savored the memories of the clear blue sky, the mountains richly painted with mineral deposits, the Bedouin campgrounds beside a small spring, the large expanse of brush against the shadow of the mountains.

The bus reached the village at dusk and my father could barely see the outline of the pomegranate gardens. Sha’ul unloaded the merchandise by the side of the dirt road and asked my father to wait for him there and not move. He was going to make sure that the gates were open and that he could secure a few donkeys to help carry the goods inside. Surprised, my father asked, “Why don’t we just drive to the gate, agha Sha’ul?”

The merchant was exhausted and impatient, his wrinkles deeper now that the sun had darkened his skin further, leaving white lines around his eyes, crinkled from the bright sun. His graying hair was matted with sand and fine dust. “First of all,” the peddler snapped, “a truck is too big to go down this road. Most passengers are on their way to Jahrom and it is getting late in this biaboon, in this forsaken place. Plus, do you want me to get killed for a few pieces of merchandise if the gates are closed? What if we have to stay outside the walls with all the bandits knowing about the goods? Stay here behind this hill. No one will see you from the road or the village. I will be back soon.” He started walking down the narrow dirt road that led to the village and slowly disappeared in the dark that gradually blanketed the landscape.

Baba waited by the road for an hour in the dark before he started to panic. Now he expected to be robbed and murdered by outlaws roaming through the desert. Totally alert, he stared into the dark, looking for a sign of life. Then his mind wandered, imagining ferocious beasts slowly closing on him, and he shivered. He heard wolves crying in the distance and his hair rose on his body; he felt something rubbing against his leg and screamed, thinking that he had been bitten by a deadly snake. Fortunately, it was just the fringes of a carpet touching his skin. After a few hours, he finally gave up on his boss; he must have been murdered by the peasants or the bandits. He shivered as the desert temperature fell rapidly.

Baba was tired and sleepy but afraid to close his eyes. After all, the same murderer could knife him in his sleep. He wrapped a large blanket around himself and paced around the pile in the dark to keep awake. He was suddenly falling. Baba screamed in terror and called for his mother in Judi, “Ahhhhhh! Mava, Mava …” He landed at the bottom of a ditch he had not seen in the dark and recited his shema, expecting death to take him. Scratched but unharmed, he decided that the fall could be a good omen. No one would look for him in the hole, and, if the robbers came by, they could steal the merchandise and disappear. He wrapped the blanket tighter around himself and surrendered to an uneasy sleep, in which wild beasts roamed the biaboon; black scorpions crawled on his blanket with their venomous tails on their backs; and bandits with black headpieces covering their faces galloped on fast horses toward him with shining eyes and drawn curved swords.

In the early hours of dawn, my father awoke sweaty with a jolt, screaming, thinking that an animal was pulling on him. But it was only his boss shaking him.

“Wake up, wake up, Esghel. We have to load the donkeys.”

“I thought you had been killed,” my father said, confused, but elated. “What happened? Why didn’t you come back for me?”

The man had rushed to the gate of the village to convince the gate-keeper to allow him extra time. But the doors were already locked for the night and the gatekeeper, along with the peasants and their animals, had retreated within the enclosure. It was too dark for him to find his way back. So he had lain by the walls that surrounded the village and had gone to sleep. Baba and his boss threw the goods on the backs of the donkeys, striking their hinds with a stick as they advanced slowly to the open doors.

The following day was Friday and at sunset, Shabbat. As the sun disappeared behind the mountains on that first day in Bab-e Anar, my father along with the merchants prepared themselves to greet the Shabbat Queen. Other peddlers from the nearby villages joined them to make the gathering of ten men necessary for praying. They washed themselves in a stream and changed their dusty clothes. In the absence of women, they poured oil into two homemade clay vessels, put wicks through their narrow openings, lit th

em, and said the prayers that were women’s obligation. Then they sat cross-legged around a sofreh, a cloth spread on the ground. One of the men uncovered a bottle of homemade raisin wine from a hiding place. Since alcoholic drinks were forbidden in Islam, the merchants had to be careful not to insult the local villagers. Two long flat breads were set on the table. They stood and softly said the kiddush, the prayer over wine in Hebrew, careful that their voices should not reach outside their hut. They washed their hands and said the prayers over bread. For the first time, my father ate a Shabbat meal away from the soothing sound of my grandfather’s prayers and the aromatic dishes that were his mother’s Sabbath specialty, and he used all his energy not to break down and cry.

After two months, Baba grew terribly homesick. Other travelers brought new merchandise and told him how his mother cried for him as well and called his name. Finally, he started running a fever and was too restless to help in the shop. The peddler gave him a few rials and sent him alone to find a bus on the side of the road. After hours of waiting, a ball of dust appeared in the horizon. A large Mercedes truck wobbled its way down the uneven rocky road to where my father was standing and stopped. Baba paid, climbed the side of the tall truck, and found a seat on the floor with other passengers, crates of watermelon, chickens, a small sheep, and strewn bundles of clothing.

At noon, the bus stopped by a caravansary, a weathered tent and a few stools in the middle of the desert. My father didn’t have any food with him, but was too shy and too afraid to go inside to ask for a drink or a piece of bread. There was a barrel of water on the side of the teahouse, but Baba feared that it was for Moslems only.

Under the scorching sun, my father’s mouth felt like the sand underneath his feet. He saw Bedouin women going down a steep slope and reappearing with jugs of water on their shoulders. The descent to the spring at the bottom of the hill was not as easy as he had thought. Although the nomads had climbed in and out of the hole with ease and grace, my father slipped and stumbled his way down. He was excited at the sight of the turquoise fluid oozing out of the floor of a cave by the side of the mountain, surrounded by greenery and reeds. Sweaty and dusty, he knelt in the muddy ground by the pool and cupped his hands to scoop the clear water to his mouth. It was deliciously sweet. He hurriedly reached with his open palms for more, but as he lifted his head this time to sip the water, he came eye to eye with a black snake, its white mouth wide open as though it were aiming for him.

Wedding Song

Wedding Song