- Home

- Farideh Goldin

Wedding Song

Wedding Song Read online

BRANDEIS SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN

Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor

Joyce Antler, Associate Editor

Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor

The Brandeis Series on Jewish Women is an innovative book series created by The Hadassah-Brandeis Institute. BSJW publishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods, of interest to scholars, and for the educated public. The series fills a major gap in Jewish learning by focusing on the lives of Jewish women and Jewish gender studies.

Marjorie Agosín, Uncertain Travelers: Conversations with Jewish Women Immigrants to America, 1999

Rahel R. Wasserfall, Women and Water: Menstruation in Jewish Life and Law, 1999

Susan Starr Sered, What Makes Women Sick: Militarism, Maternity, and Modesty in Israeli Society, 2000

Pamela S. Nadell and Jonathan D. Sarna, editors, Women and American Judaism: Historical Perspectives, 2001

Ludmila Shtern, Leaving Leningrad: The True Adventures of a Soviet Émigré, 2001

Jael Silliman, Jewish Portraits, Indian Frames: Women’s Narratives from a Diaspora of Hope, 2001

Judith R. Baskin, Midrashic Women: Formations of the Feminine in Rabbinic Literature, 2002

ChaeRan Y. Freeze, Jewish Marriage and Divorce in Imperial Russia, 2002

Mark A. Raider and Miriam B. Raider-Roth, The Plough Woman: Records of the Pioneer Women of Palestine, 2002

Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite, 2003

Kalpana Misra and Melanie S. Rich, Jewish Feminism in Israel: Some Contemporary Perspectives, 2003

Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman, 2003

Rochelle L. Millen, Women, Birth, and Death in Jewish Law and Practice, 2003

Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage, 2004

Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society, 2004

Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe, 2004

Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise, 2004

Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism, 2004

Margalit Shilo, Jewish Women in the Old Yishuv, 1840–1914, 2005

MEMOIRS OF AN IRANIAN

JEWISH WOMAN

Farideh Goldin

Brandeis University Press

Published by University Press of New England

Hanover and London

Brandeis University Press

Published by University Press of New England, One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766

© 2003 by Farideh Dayanim Goldin

www.upne.com

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Members of educational institutions and organizations wishing to photocopy any of the work for classroom use, or authors and publishers who would like to obtain permission for any of the material in the work, should contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Goldin, Farideh, 1953–

Wedding song : memoirs of an Iranian Jewish woman / Farideh Goldin.

p. cm. — (Brandeis series on Jewish women)

ISBN 1–58465–344–2 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-61168-389-9 (eBook)

1. Goldin, Farideh, 1953—Childhood and youth. 2. Jews—Iran—Shiraz—Biography.

3. Shiraz (Iran)—Biography. I. Title. II. Series.

DS135.1653G654 2003

955’.72—dc21 2003008352

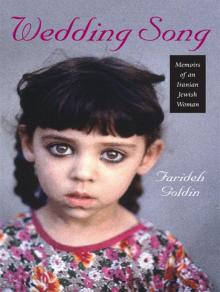

Cover photo © 2002 Steve McCurry, from Portraits. Used by permission of the photographer and Magnum Photos Inc. McCurry has covered many areas of international and civil conflict, including the Iran-Iraq war, Beruit, Cambodia, the Philippines, the Gulf War, and the disintegration of the former Yugoslavia and Afghanistan. His focus is on the human consequences of war. McCurry’s work frequently appears in National Geographic Magazine with recent articles on Yemen and the temples of Angkor Wat, Cambodia. He writes, “Most of my images are grounded in people, and I try to convey what it is like to be that person, a person caught in a broader landscape, that I guess you’ll call the human condition.” A poster of Mr. McCurry’s now iconic “Afghan Girl” is available on his website: www.stevemccurry.com. A portion of the proceeds from the sale of that poster will go towards helping the children of Afganistan.

CONTENTS

Prologue: Iranian Memoirs

1. Blood Lines

Maman: My Mother

Baba: My Father

Maman’s Story

Baba’s Story

A New Life in Shiraz

Aziza

2. My Grandmother’s House

My Childhood Home

A Day at the Hamam

The Question of Virginity

The Garden Wedding

A Divorce in the Family

3. My Education

Private Lessons: Fear

A Restless Year

The Price of a Woman’s Education

Khanom-bozorg

The First Grade

Leaving The Mahaleh

4. A Place for Me

Our New Home

My Space

Out of Place

A Piece of Chocolate

5. Marriage: A Woman’s Dream

Khastegaree: Marriage Proposals

Feathers and Hair

A Viewing

6. My New World

Leaving Iran

Bibi

A Match for Me

The Last Days

Epilogue: September 2001

Nightmares

A Closure

Acknowledgments

Glossary

This book is dedicated to my family:

My husband Norman always believed in me and gave me “a room of my own.”

My daughters Lena, Yael, and Rachel were the first to pull the stories out of the family well, rich with tradition, life-giving, yet dark and hidden. Along with my siblings and their spouses, they were my first readers. They laughed and cried with me across all these years as I tried to transform my spoken stories into written words.

My mother Rouhi, whose rouh, her soul, will forever be intertwined with mine. Maman, how could I ever try to forget you?

My father Esghel, who gave to our extended family and the Jewish community until there wasn’t anything left to give. Baba, mehila, please forgive me. I love you.

The gate to the city of Shiraz.

Prologue

IRANIAN MEMOIRS

If I had to pick one defining moment in my Iranian life, it would be 5:00 A.M. one Friday in the fall of 1968. I was fifteen. Normally I woke to the sounds of a peddler selling green almonds and fava beans from the sacks hanging on each side of his donkey, the radio screeching the latest news, our only toilet in the hallway flushing, the hustle and bustle of my mother scurrying around to prepare breakfast, to get ready for Shabbat, my grandmother asking me to get to the bakery. But that morning, a scorching odor jolted me out of a deep sleep. At first I thought someone was incinerating the trash outside; I thought my mother had burned the omelet; no, the house must be on fire. Smoke filled my room. I threw off the covers and rushed through the hazy hallway to the kitchen. The entire family was there—my mother, my grandmother, my married uncle, his wife and children, my single uncle, my single aunt, my sister and two brothers�

�trying to get their breakfast, coughing, their eyes irritated.

My father stood near the mud stove, still in his pajama bottoms and a V-neck undershirt. He was chewing his mustache, so I knew he was angry, but at what? Then I saw it. He was throwing books in the fire, my books, the books I had hidden underneath the bed, behind my clothes in the armoire, in the pocket of my winter coat.

It wasn’t as if he hadn’t warned me about reading. He had heard from cousins at my school; he had caught me reading with a flashlight in bed; he had seen me walk to school with my head in a book. He had warned me just the previous week after an aunt erupted, “Everyone in the community knows that your daughter reads nonstop, corrupting herself, giving us all a bad name.”

Instead of obeying, I became more cunning at finding places to hide my books. I couldn’t give them up; they were my escape, the keepers of my sanity. I was reading mostly French and Russian classics in translation. I didn’t quite understand them because the stories were so absolutely alien to my reality. Nevertheless, they fascinated me, introduced me to unknown cultures and captivating characters. Now curling at the edges, crumbling, the black of the words disappeared into the red of the flames and the gray of the ashes—exorcised worlds flew in tiny particles from the pyre and swirled in the air. Breathing them, I wondered where I could take my mind now that their magic had fled through the chimney. Perhaps it was time to take my physical self away to the places the books had painted for me.

Although the idea of burning books may jolt many Western readers, I don’t want my father to be judged harshly. He wasn’t trying to destroy me, but just the opposite. He thought he was saving me by indoctrinating me with the community standards. He didn’t know of another person who was addicted to books; neither did I. He told me that I was of marriagable age, that I needed to stay at home to learn to cook and clean since I couldn’t resist the corruption of the outside world.

His words weren’t new. Most of my male teachers had reiterated the same sentiments in the classroom, telling the few of us who dared to choose mathematics as our major to prepare for marriage instead of wasting educational resources that rightfully belonged to men—men who as the heads of households would have to support their families. Hearing the same philosophy from my father, however, was much more frightening.

I don’t think my father meant those words; I think he wanted to keep me in line by instilling fear of a different fate. Traditionally, a desirable candidate for marriage was a naïve girl with “closed eyes and ears,” not one who knew of the world. He didn’t want me to ruin my chances for finding the best possible husband. And in the end, my father was the force behind my higher education, insisting that I had to have a college degree to find a better husband, emphasizing that I had to be bilingual since English was the language of progress, the promise of a better future.

Later in the week, when no one was around, I uncovered my last hiding spot in the floor of an armoire, pulled out my journal, and burned the pages in the same stove. Now I was truly alone.

Since Iranian schools didn’t promote reading, I didn’t have so much as a storybook to read for three years. Then, in 1971, as a first-year student, I stepped inside the Pahlavi University library and scanned with amazement the large collection of books in translation. I promised myself I would finish reading all of them before graduating. Read, I did, but I didn’t write again until I had immigrated to the United States, married an American, and had children of my own, children who wanted to hear about my Iranian life. And I, who once had tried so hard to forget my past, went searching for our life stories to record them for my daughters, for the next generation who feared visiting the country of my birth. By then, the 1979 Islamic Revolution had forced a mass exodus of Iranian Jews, leaving nothing but the rubble of Jewish life in Iran. I could extract only fragments of recollection, both what I could recall and memories told to me by family and friends in exile, numb, lost, almost as if still wandering through the desert in a weary exodus from Egypt.

For the last seven years, I have scavenged among the “whys and whens” of our lives only to concede that I cannot fully reconstruct our past. Some of my stories are repeated with the obsession of one who cannot let go of an event, a contemplation. Others are just forgotten, disposed of, or too hurtful to retell, leaving holes in the continuum of our life narratives. These memoirs weave my recollections together with those of my parents and their families, often incomplete and sometimes contradictory.

The tales I have gathered are like the picture frame my father gave me before I left Iran. The frame is made of the intricate designs of Shiraz khatam, decorated with delicate inlaid pieces of wood and ivory arranged painstakingly to create geometric patterns as if each one were a secret map. I wrapped his present well and hid it securely under my garments on the long flight from Iran. I didn’t open the package for years. My father’s gift didn’t fit the décor of any of the apartments I lived in; it was too gaudy, too elaborate, too foreign, too difficult to open and repack as I moved from city to city. When I finally unwrapped it many years later, bits and pieces of ivory and wood were missing, ruining the congruity of its design if looked at closely. I put my wedding picture in it and hung it on our bedroom wall. I can’t see the imperfections any longer. When looked at from afar, the designs still make sense; there is a harmonious pattern to their delicate, crushed layout.

This book chronicles my childhood, my family’s lives, and the lives of women who went unnoticed in the southern Iranian city of Shiraz. I yearn to acquaint my Western readers with the essence of Jewish life in the shadow of Islam, the magnetism of Western freedoms, culture, and technology against the lulling effect of Persian thoughts, customs, and ethics.

This is my story.

Chapter One

BLOOD LINES

When I told my mother of my first period, she folded her fingers into a fist and hit herself on the chest, “Vay behalet!” She used the Farsi words as if I had angered her. “You’ll suffer,” she said.

The sun painted the walls of the bedroom I shared with her, etching shadows of the cast iron grillwork on the windows. Two cats fought outside. The water in the shallow, keyhole-shaped pool was green with pollen. I leaned against the wall by the closet, my hair still wild from storybook dreams against a soft pillow, my panties wet, my thighs sticky. My mother stood in front of me but wouldn’t look into my eyes. She looked at my left shoulder or maybe the wall.

“Misery will be your share in life, for you have become a woman with all its inheritance of pain,” she said. “This is the beginning of your sufferings. Be prepared!”

My mother’s eyes were the shade of young dates on a palm tree, hazel with striations of gold. Her curls were unruly, her palms the surface of the desert.

I bit the inner flesh of my lips. There was blood in my mouth. I wondered about this mysterious prophecy of catastrophe. Could I find an antidote to the poison my mother believed would ruin me? A sparrow skidded on the murky water in the pond. Did it think the surface was solid? It flapped its wings in a panic and landed on a water fountain in the middle.

A bundle of rags lay on the closet floor like a sleeping cat. My mother crouched, grabbed an old sheet, put it between her teeth, and tore it with her claws. “There!” With her shoulders stooped, she turned her back and closed the door behind her.

When I entered the passage to womanhood in spring of 1966, I was thirteen years old. In our Jewish home in Shiraz, the monthly occurrence was both intensely private and offensively public. Men never mentioned it. Women spoke about it in hushed voices while shelling fava beans, when rolling mung beans on a round brass platter to separate them from pebbles.

Someone’s daughter had started her first period; she was ripe to get married. Disregarding the Jewish laws of family purity, a neighbor’s lustful husband wouldn’t leave her alone, so she took her rag to the community leader to prove that she was still bleeding, to seek his protection. Speaking of blood, the women covered their mouths with the palms of

their hands as if trying to shove the words back, as if the language itself could pollute the air.

During my childhood, I often answered the dreadful call from various women in the family, “Farideh, come. Come to the bathroom and pour water over my hands.” Pouring water was the euphemism for helping them wash their rags and bloody underwear. With an aftabeh, a copper water jug used for washing our bottoms, I bent over my mother. She wrapped her skirt tightly around herself and squatted by the hole in the ground that was our toilet. In a slow constant flow, I poured water over her hands as she rubbed the leftover soap into the unclean clothes. She didn’t use the sink or the wash tub or else they would be contaminated with her gha’edeh, her monthly “mandate.” She wrapped the clean tamei clothes in newspapers, took them outside, and hung them on shrubs in the backyard. When she came back, I helped her wash her hands again over the toilet before she dared to wash them once more in the sink.

Passover was the most difficult time for menstruating women. My mother always mumbled curses underneath her breath, made faces drinking the bitter spinach juice to delay her period. Otherwise, she could not hold the Seder plate as adults did, reciting “Ha-lakhma … This is the bread of affliction … Now we are slaves; next year may we be free.” Otherwise, she could not dip her bitter herb in the same bowl of salt water, the tears of our ancestors, like everyone else.

“Damned be the day I was born a woman!” My mother hit her chest whenever she had her period during Passover. “There is nothing for a woman but sorrow and pain!”

As the customs dictated, when menstruating my mother had to drag the tamei mattress, pillow, and quilt out of the special closet and spread them in a corner of the bedroom, away from the traffic. I wondered whether she minded that part of the custom. Her impure corner gave her a little space of her own that no one approached for fear of becoming unclean. My grandmother didn’t ask her to rise from her warm bed to make her tea. My father didn’t tell her to prepare his breakfast at five in the morning before he went to work.

Wedding Song

Wedding Song