- Home

- Farideh Goldin

Wedding Song Page 2

Wedding Song Read online

Page 2

Left alone, sometimes she wrote a letter to her parents. Sometimes she read. Sometimes she sang a song to herself.

My father took the bed at these times. My siblings and I huddled under the blankets in another corner of the bedroom floor. There was a taboo space around our mother where no one dared to intrude. Somehow even the air touching her body contracted the same invisible filth. She ate from plates that had to be washed separately and stored in a hidden space, where no one could touch them by mistake.

I knew all the rules of the monthly curse, the separation, the untouchability, the fatigue, and the blood. They should all have been frightening. Yet when my turn came, something was different. That early morning, when I withdrew my hands from the wetness between my legs, I was not terrified of the blood. I was euphoric. I felt grown up. Now my grandmother wouldn’t allow me to bend over with the low broom sweeping the carpets. I counted on her repeating to me what she used to tell my single aunt Fereshteh, “Go lie down. Your back must be hurting from the flow. Go rest.”

Now someone had to bend over the toilet pouring water over my hands to wash my soiled underwear. Now I would not be sent out of the room when women gathered to gossip. I was going to be a part of the sisterhood of women. Even with all my mother’s warnings, I could not help the ebullience that surged in me.

I knew the secret was out when I went into the kitchen that morning. The men, my father and two uncles, were at work. The women sat on low wooden stools, their skirts tightly wrapped around their legs. My mother mixed grated cooked potatoes, ground beef, and eggs. She took small portions out of the mixture, flattened them between the palms of her hands, and put them in the frying pan on top of a kerosene stove with sesame oil and turmeric to make shamee. I loved to hang around for the broken pieces. My mouth watered. Geeta, Uncle Morad’s wife, and the bane of my mother’s life, chopped tomatoes, cucumbers, parsley, and onions to make a Shirazi salad. That was my job. She had a meaningful smile on her face. She knew.

Picking through the vegetables for a stew, my grandmother looked like a flower amidst a garden of herbs. “Don’t touch, don’t touch,” she said.

I hadn’t tried to handle anything. Her calico kerchief slipped off her hair at the sudden gesture, revealing two henna-covered braids. She didn’t have her teeth in her mouth. Her words slurred and came at me in slow-moving waves.

It was Friday, my only day off from school, the busiest day in the kitchen before the start of Shabbat. Any other week, my help would have been welcomed, orders given rapidly to wash and clean, to chop and mix. Now I was a nuisance.

Knowing of this reaction, I wondered if my mother had betrayed me by not warning me to hide the secret of my blood; if she had abandoned me by exposing my secret herself. How I had convinced myself that I would be different! I couldn’t look at her.

Khanom-bozorg, my grandmother, tried to find a job away from the food area for me. “You can sweep the backyard.”

I grabbed a low broom, but lingered by the door. The pots clanked, the water gurgled down the sink, the oil sizzled, the charcoal popped in the mud stove, and sparks flew around a large pot of water. My mother poured the rice in, counting aloud five cups. In comparison, the backyard felt like such a lonely place. Khanom-bozorg must have noticed the sadness and hurt on my face. “Go stand in front of an orange tree and tell it, ‘Your greenness shall be mine, my yellowness yours,’” she said. “That should bring you luck, a good husband.”

Geeta covered her mouth with her parsley-stained hand and snickered. She spurned me as an extension of her dislike for her sister-in-law. I wished I could free myself from the blood that linked me to my mother, for she was the carrier of my oppression.

In our large garden, I looked at the long rows of orange, tangerine, sweet lemon, pomelo, and sour orange trees lined up against the two walls. Sweet lemons were precious for their medicinal magic. They had to be wrapped each winter to save their delicate limbs from frostbite. Pomelos were reserved for special guests only since they were so rare, large and beautiful. Sour oranges were used for flavoring the food. Their fruits were too tart to eat but every Iranian dish tasted better, more complete with them.

I recalled watching my father cut a sour-orange tree halfway down the trunk, gently make an incision to place a cutting from a tangerine tree. All our trees originated from their species that were hardy and immune to drought and disease. A delicate wind swirled around the tree-lined courtyard, mixing the fragrances of orange blossoms and roses. I chose the tallest sour orange tree, stood in front of it, and wished to be as strong as it was, to stand erect as it did, not bending to the whim of others. I wished to be like its fruit, adding flavor to life, yet tasting so pungent that no one would dare to bite into me.

I went back to the house to face the other women. I took the kettle and made myself tea with the orange blossoms I had snipped from my tree. As I reached for a regular cup, the women stopped their work and stared at me. My grandmother rose half way, but sat down again. She looked at my mother and shook her head. “Rouhi, you didn’t show your child where the tamei dishes are!”

I had failed my first lesson in womanhood.

My mother grabbed my arm. “Why are you making trouble for me?” she asked. “Don’t I already have enough to put up with?”

I didn’t care. Since they had made me an outsider, I detached myself from their rules. After the initial hurt, I was content, determined to be different, to look inside myself rather than to their world for answers. I would use another dish the next time and another the time after that. I would wash my underwear in the bathroom sink with good soap and sleep on my own mattress. Let them all be tamei, impure, every day and forever.

That night I unrolled my own mattress on the carpet in my usual spot. I fell asleep in the cool breeze from the open window. My parents’ whispering woke me up. In the pitch-darkness, phosphate dots shone on a round alarm clock by their bed. “Your daughter’s misery has started,” my mother said. “Pity on her who will soon know the cruelty of life.”

I listened for my father’s response, but it never came. I buried my face in the pillow and cried silently. It was all too much—the humiliation of something so private being discussed with my father, the loneliness of being separated from the women whose company I desired. My younger sister, Nahid, rolled to her side and faced me. Her big eyes looked darker than the night. She moved closer to cuddle. I caressed her sweaty hair. We were on a long voyage against the strong tides of superstition and female inferiority, lonely, without our mother.

Maman: My Mother

My mother was born two years old. My grandparents’ first child was a daughter, named Rouhi. When she died a toddler, they kept her birth certificate and gave it to their next child. Therefore, when my father and his brother-in-law, Masood, knocked at their door thirteen years later to ask for Rouhi’s hand in marriage, she was legally of marriageable age.

If my mother didn’t have her deceased sister’s birth certificate, I am sure my maternal grandmother would have found a way to circumvent the law. Girls were married young. Most officials helped families get around the law that forbade child-marriages. My great uncle, Agha-jaan, crossed his hands over his chest and laughed when he recollected his own story of changing his bride’s birth certificate. He approached an official to whom he sold fabric at discounted prices. This man told my great uncle to dress his twelve-year-old fiancée in a mature outfit: long skirt, jacket, hat, and high heels. They appeared at the official’s door with the young girl made up, kohl around her eyes, and red lipstick smeared on her mouth, slipping and losing control while walking in the unfamiliar spiked shoes two sizes larger than her feet. She refused to hold hands with Agha-jaan, but when asked if she was willing to marry this man, she said yes obediently. She was then pronounced to be legally fifteen and her birth certificate was changed.

Although my great uncle’s bride was a child, she had her family close by to check on her. Her parents’ home was a refuge even if for short periods

of time. My mother was alone. She was given away as a young bride to a man from a far-away city. My parents’ official date and place of marriage is 17 October 1951 in Shiraz, but that was a formality they went through when in my father’s hometown. The religious ceremony was performed earlier in Hamedan. She was thirteen, he twenty-three.

All my life, I have struggled to understand and accept this implausible union. Many times I have imagined standing outside my parents’ bedroom on the night of their wedding in Hamedan, never daring to turn the knob. I couldn’t. I didn’t want to see beyond the doors where a young man lay with a child-woman for the first time. I never asked my father or mother about their first night together. My mother would have shared the events, but I didn’t want to know.

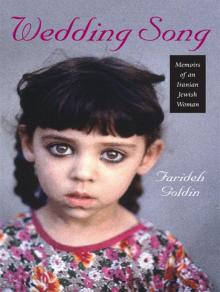

Maman in Shiraz after her wedding. My mother wears jewelry given to her as a wedding gift. My father made the gold pin in the shape of two roses, studded with fresh water pearls.

I do, however, know what my great uncle Agha-jaan once said of his child-bride. She wouldn’t let him touch her. Although she had obediently agreed to the marriage, she screamed and wept on their wedding night, wanting to go home, to sleep in her own bed. Even when an older sister went in to sleep between them, the bride was restless and crying. My great uncle remembered his own outrage. He was young; his body burned. This was, after all, his right. She was his wife!

He beat her up. She still resisted him. He forced himself on her. “She eventually came to understand my needs. She became a good wife,” he said.

My mother had her first period away from her mother, far away from home at my father’s house. She had been married to him for almost a year. Maman approached her mother-in-law with the news, her head bowed low in embarrassment. Khanom-bozorg told her not to touch the food, or wash the dishes, or sleep in the same bed with my father. She showed my mother the closet where the tamei mattress was stored, stinking of old blood and sweat. Maman wrapped herself in her winter coat and slept on the floor. I wonder what my grandmother’s reaction was to her daughter-in-law’s news. For a few days each month, she would miss a pair of hands to help with the women’s daily work. It also meant that my mother could get pregnant and produce grandchildren, preferably sons. Instead, a year later, I was her firstborn, a girl.

Baba: My Father

Like my mother, my father is also the oldest child from a second marriage. My paternal grandfather’s first wife had the familiar fate of so many women of the era who died in childbirth. He had to find a wife quickly to take care of the newborn and two older children. He chose Tavous, who was fifteen years old at the time and a divorcée. She was young with strong legs and arms for hard work and wide hips perfect for giving birth to eight children.

Then, when my father was eighteen, his father died of a simple infection and left him with the responsibility of his mother and seven siblings. As the great rabbi and the communal judge for the Jews of Shiraz, my grandfather had earned the unquestioned respect of both Jews and Moslems. He forgave his fees for weddings and circumcisions if the families were poor. Slaughtering the cows as the community shokhet, he let go of his earnings if the animal proved to be unkosher due to lesions in its lungs, recognizing the loss of the poor butcher who unknowingly had bought the unusable animal. My paternal grandfather felt honored that, like his father and grandfathers before him, he had been chosen to serve and guide the Jewish community. Therefore, after an emotional day during which the community closed down to take turns carrying his coffin from the ghetto to the cemetery, after the boys from the Jewish school walked in front of his coffin with lit candles singing Tehilim, after the seven days of shiva, when everyone brought food and comforted the young widow and her children, all that was left to my grandfather’s family was the respect, love, and the devotion of those who had known him.

Baba at the time of his marriage.

Members of the Jewish community kept reminding my father that he was a grown man with great responsibilities, that he had to sacrifice his needs to safeguard his mother and seven siblings. Once, as he ate an ice cream sandwich by a kiosk, a distant relative spotted Baba and hit him on the head, saying that my father was stealing food from his own sisters and brothers. Leaving a movie theatre, he was admonished by a community elder for his selfishness. Baba learned to let go of his individualism and to see himself as the core of the family unit, whose sole job was to keep them together, and to help them succeed where he could not himself. Later my father expected his own children and wife to live by the same principles of selflessness. We had to exemplify community standards and meet the expectations of the extended family.

My father’s problems were exacerbated when his mother Tavous started showing signs of emotional breakdown after her husband’s death. Periodically she struggled to catch her breath, fainted, and had to stay in bed for days. There was no one to run the household. The attacks, many of which I witnessed myself, continued throughout my grandmother’s life. I think a modern term for them would be anxiety or panic attacks. She was left a pauper in her mid-thirties with a huge debt accumulated by my grandfather’s lengthy illness. With eight hungry children, the youngest only a toddler, Tavous had every reason to be panic-stricken.

Baba approached a few friends and relatives for financial help, but they rejected him. Instead, they suggested that he should apprentice the young boys to shopkeepers and peddlers. Baba refused. Two of his sisters were married very young, partly to alleviate the back-breaking expenses. My father himself had given up his dream of becoming a physician. He decided the younger brothers would fulfill his dreams for him, and no sacrifice to accomplish this would be too great.

My father told me of his struggles to find a job to pay off the debts and feed the younger children. His eyes teared when he remembered betrayals by family members and kindness from strangers. A Moslem man trusted my father with a bag of gold, his first real assignment as a goldsmith. Knowing that this job would determine his reputation as an artisan and an honest man, Baba slept in his workshop to protect the gold. His diligence paid off, and five years after my grandfather’s death, my father had an established business making gold jewelry. He told his brother Morad that he must join him in providing for the family. The two worked at a small shop two blocks from the mahaleh, the Jewish ghetto, where they lived in my grandfather’s house with all but two sisters who married around puberty.

Finally there was food on the table, but my grandmother suffered with the burden of housework. When her “asthma” attacks increased, her married daughters had to leave their own families and rush to the house to nurse her, causing tension with their husbands’ families. My father knew it was time for him to get married, to start a family, and at the same time, to relieve his mother of the grueling daily work of cooking and cleaning.

Baba did try to find a wife with a good social standing in Shiraz. Although the community admired my father’s devotion to his family, they wouldn’t give him one of their daughters in matrimony, dreading the life of poverty and servitude that my father’s bride would endure. My aunts and uncles understood the importance of this decision as well and worried for their own welfare. Soon Baba realized that he must find a wife whose family could not question his larger commitments.

Less than a decade after the devastation of World War II, Iran was an impoverished country in shambles. Being financial burdens, Jewish girls were married off to any men within the religion who could feed them. A bride for my father, the family elders suggested, should come from outside the Shirazi community to ensure unobtrusive in-laws. Someone in Shiraz knew someone in Tehran who knew of a family in the Jewish ghetto willing to send their daughter away. My father’s brother-in-law, his sister’s husband Masood, volunteered to take him to Tehran. The one-day trip by bus took them through narrow passes wrapped around mountains, a most adventurous endeavor for both of them.

In Tehran, they found the house and introduced themselves as khastegars, seekers of a bride. The family welcomed them, and asked them to take their shoes off and res

t against the pillows on the floor. Someone brought them tea, flower-essence drinks, and chickpea cookies. Soon family and friends gathered in the house, filling it with their sounds of joy, ululating, clapping, and singing wedding songs. My father heard someone being sent to get the rabbi to perform the wedding, and he realized that he was going to be married to a woman he hadn’t met.

Masood told me years later, “We had two feet, borrowed another two, put our tails on our backs and ran out of the house with our shoes underneath our arms.”

When recounting the incident, my father couldn’t stop laughing. “I don’t know what kind of a girl they were going to glue on me,” he said. “I didn’t know if she was blind, bald, disabled, or old, but I wasn’t going to wait around to find out.”

The residents of the mahaleh must have been bewildered by the sight of two strangers running in the narrow alleyways with their shoes under their armpits and little travel bundles over their shoulders. But that day, being young, inexperienced, and having never left their city before, my father and Masood panicked. They worried that as revenge someone would report them to the authorities, falsely claiming that they had stolen from the Tehrani family’s house.

Fearing the family’s wrath, they decided to leave Tehran. Masood suggested a pilgrimage to the tombs of the Jewish heroes Esther and Mordekhai in the mountainous city of Hamedan. He also suggested that they find the Jewish school and wait outside to see if any of the girls looked suitable. When the school let out, the two men followed one of the girls home. In Masood’s version of the story, he pointed to a bouncy girl. “That’s a girl for you,” he told my father.

Wedding Song

Wedding Song