- Home

- Farideh Goldin

Wedding Song Page 8

Wedding Song Read online

Page 8

What about my mother? I thought. What about her?

The Garden Wedding

As my mother despaired and retreated into deeper silences, I became even closer to my grandmother, learning from her, getting to know the world around me, escaping my mother’s increasing gloom. That year, Khanombozorg was excited because my aunt Shekoofeh was engaged.

Shekoofeh had qualities that Iranian men favored: black hair that contrasted with her fair, clear skin, and a curvaceous body that was noticeable even underneath her modest clothing. She wore an air of optimism, smiled gently, and practiced lady-like manners. Being a good student, Shekoofeh cried and begged to be allowed to finish her last year of high school, but the decision was made for her.

My grandmother chose me to help her shop for the dowry. In the indoor bazaar, I held tight to a corner of her chador, not wanting to lose her among the masses of shoppers. My neck hurt from looking up at the vaulted bazaar, decorated with handmade bricks and colorful mosaics. Light glowed through windows beneath the ceiling. I kept bumping into people as I stretched my neck to see stalls filled with Persian carpets, Indian silk, tribal sheep-skin coats and hats. Burlap bags of spices, turmeric, saffron, cloves, and cardamom lined up beside bags of herbal teas.

On the first shopping day, my grandmother and I found our way to the silversmiths’ market, looking for the best quality silver and craftsmanship at the lowest price. She inquired from a shopkeeper, “How much for a bride’s package?”

As she bargained, I amused myself watching passersby. I joined a laughing crowd to see what was so funny. A mule had stuck its feet in the dirt floor of the bazaar and refused commands to move forward. The more the owner pulled on the noose, the harder he hit it with a stick, the more stubborn the mule became, leaning backward on his hind legs until its cargo of charcoal slipped and fell behind it. The owner screamed and gave the mule a good beating. The animal let go of its bowels on top of the coal. I was laughing with the rest of crowd when I felt a hand on my back, pulling on my sweater. Then I heard my grandmother, “You want to get lost? You want these men to kidnap you for slavery? Didn’t I tell you not to wander off?” I was scared that she would report my behavior to my father, but she was preoccupied with other thoughts, grumbling, “Calling me a cheap Jew! The thief! Najes himself, calling me impure, he with goh on his underwear! He doesn’t know how to wipe his own behind and calls me dirty.”

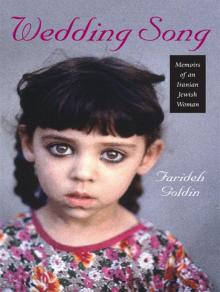

Maman, my sister Nahid, and me at my aunt’s garden wedding.

Watching the stubborn mule, I had missed Khanom-bozorg’s interaction with the silversmith. We went from one shop to another until she found a respectful person who offered the right price. I was amazed that my aunt’s hairbrush, her wooden comb, and the pumice stone were to be encased in silver; I couldn’t imagine such beauty. Perhaps being a bride was not such a bad thing after all.

When we returned home, the engagement was off. Shekoofeh had visited her fiancé’s family and refused to marry a man who lived with his parents, brothers, and their families. My grandmother and father agreed with her. They didn’t want her to have a situation similar to my mother’s, I guess. And who could blame them? The shopping came to halt.

But the shopping and the frustration had taken a toll on my grandmother’s health. Sleepless, she moaned and struggled to fill her lungs with air all night. My father took her to Tehran, visiting doctors and touring the city to improve my grandmother’s anxiety-related attacks.

At this time, my mother’s family had moved to the capital, which was much closer to Shiraz than her hometown of Hamedan. Still, my mother had not seen her family for a long time and would have loved to accompany my father and grandmother to Tehran to visit her parents and brothers. Instead, she stayed behind to take care of me, my infant sister Nahid, and the aunts and uncles who lived with us. She slammed the pots as she washed them; she didn’t bother to rinse the clothes well before throwing them on the laundry line; she burned the shirts under the charcoal iron as she sobbed, homesick.

To make matters worse, once in a while she received a letter from my father, who wrote on behalf of my grandmother to remind her of her duties: “Don’t forget to take food to Bibi.” Over and over, my grandmother ordered Maman to take care of my great-grandmother.

Grumbling, my mother sent me to deliver the bundles of food to my great-grandmother, although I was barely six. I hated passing through the narrow unpaved mazes of alleys lined with small stalls, jostled by shoppers with woven plastic bags filled with vegetables, prostitutes with bright red mouths, villagers, peddlers following watermelon-loaded mules, and rarely a familiar face. The crowd jammed the space between the tall walls and bumped and stared at me as I tried to find a landmark leading to the small door of Bibi’s house.

That was a period of hardship and absolute loneliness for my mother. Morad showed his resentment at having to work alone to support the family by giving extra orders to my mother. Overwhelmed with two young children, Maman envied her sisters-in-law who used school work as an excuse not to help her. When my father and grandmother returned with gifts of beautiful dresses for both Shekoofeh and Fereshteh, but nothing for my mother, she despaired.

Upon their return, the elders from the suitor’s family, the khastegars, came often to talk with them. Each time, they trotted to our common room and sat cross-legged, leaning their backs against large pillows. My mother ran out to the bakery for cookies, and I served them tea and sugar cubes.

As the negotiations continued, Shekoofeh hoped that with the delays she could still graduate from high school, but the principal found out about her engagement and would not allow her back. Once a woman came in close proximity to a man, she already knew too much and could corrupt the innocent virgins. There were rumors that the groom’s family had alerted the school when the engagement was broken off in order to press for reconciliation when school was no longer an option.

Finally, both families agreed that although it was impossible for Shekoofeh to have a separate house, the groom would create a separate space for his bride by adding a bathroom and a kitchen on the second floor of the house that he shared with his mother and siblings. My grandmother resumed her shopping to assemble a dowry.

The banging of metal against metal could be heard long before we entered the coppersmiths’ bazaar. Far from the main market place, this section lacked the protection of a roof and the beauty of handmade tiles and arched doorways. It was the most chaotic section of the bazaar. Donkeys carried loads of metal, fabric, or fruit through the crowd of shoppers and workers, littering the place with their droppings, which accumulated until the city workers cleaned the ground at the end of the day.

I was surprised to see so many teenagers kneeling on the dirt floor hammering at utensils. Apprenticeship was their schooling, and I was frightened by such a fate. I kept away from them, as if their future could rub off on me and leave a residue of misfortune and hopelessness. Khanombozorg found the best price for the pots that we had brought from our home and traded them for new ones to go with the bride to her home. Hanging onto the corner of her chador, I turned my head and watched the boys hammering as we walked away.

Since we had traded away our nicest pots, we had to use cheaper ones at home ourselves. Years later, when I was browsing in an antique shop in New York City, I would realize what treasures we had given away. That day, however, I was merely enjoying the sights, sounds, and smells of various parts of the market.

Back in the main section, we saw a group of Ghashghai women, a nomadic tribe outside Shiraz. They were known to be tough women, who could move herds of sheep over the mountains on horseback, a rifle on one shoulder and a baby on the other. I had mostly known women who seemed powerless and defeated by life. I looked at these nomadic women in awe. They walked tall and regally, their strong presence claiming the ownership of the space they occupied. Strong, beautiful, and feminine, they wore many layers of long puffy skirts in colors of the desert, of the mineral deposits of the mountains surrounding our city: rust, purple, yell

ow, maroon. Silk scarves, bordered with gold coins, covered their raven hair and shoulders; peacock-colored sashes wrapped around their foreheads and tied loosely in the back of their necks. The group passed us, creating music with the jingle of their gold bangles and anklets. Their many rustling skirts gently stirred the spiced air of the bazaar.

Finally, the shopping was done. The bride’s quilts were specially designed and handmade with beautiful geometric stitching, filled with clean whipped cotton, and covered with blue satin. Pots and pans gleamed; the silver-covered toiletries were delicate and regal; and new clothes, trimmed with ribbons, were ready for everyone, including me.

I watched with excitement as a few strong men stopped by the house, packed and loaded the dowry on top of their heads, and paraded them down the street to the groom’s family. In return, many large trays of sweets arrived carefully balanced on the heads of the baker’s apprentices. Delicate chickpea cookies shaped like clover leaves, puff pastry bows, raisin cookies, and bamieh were all arranged patiently and artistically in gigantic pyramids. The trays were marched through the streets so that everyone could admire the generosity of the groom’s family.

Shekoofeh’s wedding was the first one in the family since my grandfather had passed away. My grandmother decided that a garden wedding would be best since our house in the ghetto was too modest for such an auspicious ceremony.

My father hired a large truck with a canvas-covered back to take the fruit, vegetables, and meat to a garden outside town. Neighbors helped load Persian carpets and kilims, some ours and some borrowed; then they put me in the back to “be a big girl” and watch the food. I sat there in my pretty white dress, my baby sister Nahid on my lap. I arranged her dress around her hip to hide the long incision that had drained an infection after her birth. My mother gave me two bottles and asked me tend to her. I wasn’t sure if I was really being a big girl or if they wanted to get rid of me. Partly, I was sad to leave all the excitement at home; yet I was delighted to be the first one at the garden to watch the wedding preparations.

On the dusty, unpaved road, my sister cried nonstop. I fed her one bottle to quiet her despite orders from my mother to save the milk for later. Then the other bottle fell over and the milk splattered all over the place. I didn’t know if I needed to be more anxious about losing the baby food or for spilling milk over food designated “meat,” which had to be separated from dairy. When my mother finally arrived, I tossed her the baby and the empty bottles and left quickly before she could scold me.

I went snooping around to see what all the excitement was about. There were huge pots set up on top of makeshift charcoal-burning stoves to prepare the rice and stews. The aroma of chopped dill, coriander, and fenugreek mixed with the scent of chickens braised with caramelized onions and turmeric. A cook with stubble and a friendly face was alternating beef and onions on a skewer. Noticing me, he gave me an apple and shooed me away. Fruit trees and grapevines shaded the Persian carpets spread by a stream. The guests leaned against large pillows; a few recited poetry or harmonized with the musicians.

My aunt finally arrived with her future husband, passing between two rows of friends and family. Men clapped. A few women cupped their hands over their mouths, rolled their tongues and ululated, when the others sang wedding songs.

We have come to take the bride away and isn’t she beautiful!

Are the alleyways narrow? Yes indeed!

Is the bride beautiful? Yes indeed!

Don’t touch her hair for it is braided with pearls, yes indeed!

Actually, my aunt’s hair was decorated not with pearls but with white feathers shaped into a halo. Her white silk bridal gown shimmered in the glow of sun filtering through the trees in the garden. Shekoofeh’s eyebrows were tweezed into thin fashionable lines, and she wore makeup for the first time. Her provocative bright red lipstick contrasted with her demure body language—head slightly bowed in shyness, eyes lowered in virginal modesty.

When she reached the carpeted area, her sister Fereshteh helped her to sit on a Persian carpet, and fluffed her skirt around her for a picture. She was a romantic sight, bringing the wedding song to life. She sat there most of the day, looking pretty and finally let me touch her dress and feathers.

At first, she refused every food offering, afraid that even a taste would smudge her lip color. Aunt Fereshteh asked me to help the bride with her meal. Every time Shekoofeh opened her mouth for a spoonful of rice, I giggled, feeling like a mother bird feeding a chick in her nest. When she was finished, I picked at the leftovers and looked for something else to do.

Two belly dancers with colorful dresses entertained the guests. They changed behind a makeshift curtain sheltered between the trees. Fascinated by their costumes, I sneaked behind the curtains to watch them change, and was surprised to find out that I wasn’t the only one interested. A dancer pushed me out, along with male guests who had had too much aragh with their kabobs.

My mother found me and told me to join a group of women who were eating and smoking a waterpipe. She put a plate of chicken, rice, and fava beans in front of me. As I nibbled, I scanned the area for action.

Someone shouted for towels to be sent to the far side of the gardens. Apparently a few men, including my father, had decided to refresh themselves in a water hole. I jumped up and volunteered. I would have liked the women to have a turn as well, but that wasn’t modest. I lingered to watch the men exit the water in their wet underwear. They got out one after another to jump back into the shallow water again. They all looked down at themselves first, then at me with a smile, and I smiled back. My father called my mother, who dragged me away.

Eventually, it was dusk and the party had to end. My father, acting as his sister’s guardian, wrapped a piece of silk cloth around her waist, symbolically giving her away. They hugged tearfully. The groom took away my aunt in a black Mercedes decorated with flowers. My grandmother and aunts followed them, singing and clapping, tears streaming down their faces.

The musicians and dancers packed and left. The carpets were rolled and loaded again onto the truck. I climbed in there and fell asleep, dreaming of white satin and feathers, the soft rhythm of Persian music, and my aunts singing vasoonak.

My grumbling stomach woke me up from my dreams on the way home, a reminder that I had been too busy with curiosity to make time for food. The leftovers had been given to the workers. There would be no food at home. After such a bountiful day filled with food, fun, and beauty, I was starving. I looked at my mother sitting across from me with the baby at her breast, a vacant look in her eyes. Her hunger differed from mine.

A Divorce in the Family

Little pieces of gloom lodged inside my mother like prickly thorns flown in the wind from the desert surrounding our city. The happiness of Shekoofeh’s lavish wedding worsened Maman’s mental state. She mumbled about her own wedding once in a while when she thought no one was around.

A widowed woman, Anbari, and her daughter came to our house once a week to help with the time-consuming, back-breaking job of washing the clothes. They carried water from the kitchen across the yard to the cooler basement, filled the basins, and soaked the dirtier pieces in the warm, soapy water. They set up laundry lines next to the summer platform by the musk rose tree.

Khanom-bozorg had my mother sit at the basin with the laundry women, and I helped with carrying and hanging the clothes. My grandmother brought in two organza dresses belonging to my aunts Fereshteh and Shekoofeh, the same dresses that were gifts from Tehran. I don’t remember why Shekoofeh’s dress was at our house since she was already married. Homesick, she visited often, and my grandmother was probably trying to ease her load. She told my mother to wash them first, separately, and with more care.

The washer-woman stared at the dresses and, when my grandmother was gone, asked my mother, “Ma’am, which one is yours?”

“Neither one,” Maman sighed. “I don’t have any dresses like those. They both belong to my sisters-in-law.”

&n

bsp; There was a twinkle of understanding in the washer-woman’s eyes. A moment of uncomfortable silence marked the unspoken reality that a certain boundary had been crossed. Sharing any grief with these strangers, who went from home to home and gossiped, could taint the family myth of tranquility and shared love. The washer-women, notorious for their gossiping, had a precious piece of information that they could expand and talk about at various homes in the neighborhood. My mother knew that she was responsible for that opening, for showing her hurt, for having to care for clothes that she could not herself afford; and I, even as a child, recognized the problem. All day I thought about what it meant.

That night, the women gathered in a room on the second floor that served as a living room, dining room, and bedroom for my grandmother, aunt, and uncle Morad. Waiting for the men to return from work, Khanombozorg put a few little potatoes under the ashes of the coals in the charcoal brazier. My mouth watered. Maybe I thought that I could get one as a reward without begging. Maybe I wanted to get at my mother. I don’t know why, but the treacherous words just spilled out of me: “You know what Maman said to the washer-woman today, Khanom-bozorg?”

She smiled at me with both her mouth and eyes. “What? What did she say?”

My mother’s face had a frightened look. She stopped chopping the vegetables and pointed the wide knife toward me. “Stop it,” she said, “I didn’t say anything.”

Wedding Song

Wedding Song