- Home

- Farideh Goldin

Wedding Song Page 10

Wedding Song Read online

Page 10

The orders were not to talk at all. The hint of a Jewish accent could bring trouble. Trying to act invisible, the older women directed us to a large tree close to a gate so small that even I had to bend down to exit the ghetto. The tree provided a sense of security, allowing us to huddle against it and feel less noticeable. All this preparation and the anticipation of a potentially dangerous event caused my heart to pump blood faster even before the march started.

The total darkness of the street was eerie. A few street lamps usually broke the blackness with their yellowish glow, but on that night these were turned off. Women’s black chadors, and the men’s dark clothing made the darkness even deeper. The silence of hundreds gathered on the parade route added to the blackness of the night.

The flickering of dim lights in the distance announced the approach of the parade. Soon hundreds of men, their faces invisible in the darkness and their battered bodies wrapped in white burial shrouds, moved down the street. It was a march of the living dead. They shuffled their way to the tomb of the prophet looking for victims’ body parts to take for Imam Zaman, the Imam of the “time to come.” On the Day of Judgment, as it was told, limbs would come together to return the righteous men to the Garden of Eden. The symbolic act of gathering the bloodied body parts was to remind God of the sacrifice of the best, of the holiest. In return, God would resurrect the invisible Imam through whom man himself would be returned to life.

The human shrouds stretched in groups of twenty or more across the wide street, walking slowly, chanting Arabic verses from the Koran, reciting melancholy Persian poetry, announcing the night of Ashura in a haunting murmur. They carried long candles that slowly melted, giving little light. In the total darkness, the two sources of light became one; the Earth joined the heavens. The twinkle of the small flames connected the street with the black sky of Shiraz, covered with stars.

As the last of the dead passed, our small group came to life. Moving away from the tree, we found our way to the small gate, bent down one by one, and merged with the greater darkness of the mahaleh.

A Restless Year

That grim darkness of the mahaleh, not just of fearful nights but of poverty, disease and illiteracy, made an environment from which my father wished to free his children. He desperately wanted to prevent us from adopting the dialect, the accent, and the body language of our denigrated people, to let us grow up not in dirt alleyways but beside tree-lined avenues.

He supported his two brothers, who studied medicine in Tehran, and was proud of them as if they were his own children. They fulfilled his own dreams of learning a trade that could not be taken away, an accomplishment that neither I nor my siblings would ever match. Consequently, we grew up in constant need of his approval that never came, and, in the shadow of the ideal uncles, we struggled for love and approval that rarely materialized.

During my childhood, the visits of these beloved uncles created excitement in our monotonous lives. At the end of one spring term, they arrived from Tehran with special gifts for us: a box of pastel-color toothbrushes, and tubes of what I then learned to be toothpaste. I brushed and brushed my teeth with the minty paste, then I ran around with my mouth wide open to feel the rush of air against its coolness.

They also brought me a fancy white dress with wide ruffled straps, a most beautiful dress, perfect for my first-grade pictures. I couldn’t wait. Aunt Fereshteh trimmed my bangs to get them out of my eyes, and curled my hair. I felt like an aroosak, a little bride, a Persian doll. I ran down the street to my father’s shop, right next to the photography studio. I fluffed up the ruffles around the skirt, shook my hair to feel the long curls, and wished my aunt had not wiped the lipstick off my mouth. I felt as if I were a flower girl at Queen Farah’s wedding to the Shah.

My father was melting bits of gold with a jeweler’s torch to fuse a rose-shaped ornament on a bracelet. He looked up from underneath his metal face-shield with a look of surprise. “I can’t believe your mother sent you out looking like this,” he said. “Who saw you? Anyone you recognized? What will the community say about my daughter prancing around immodestly? Go home!”

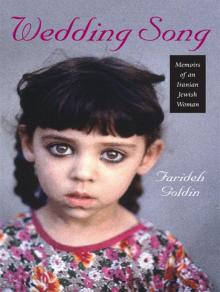

My first-grade picture.

I turned my back to leave, biting my lower lip, swallowing hard the lump in the back of my throat.

“No, wait,” my father said. He removed his apron, turned off the jeweler’s torch, hid the gold in a drawer underneath his bench, and asked my uncle to watch over the shop.

I tried to straighten my hair, feeling naked. The apprentices stared at me from behind the glass divider and smiled. I didn’t like their smiles or my uncle’s.

Baba put his jacket over my shoulders, chaperoned me home, and waited for me to wet my hair.

My mother giggled when she saw us. “I didn’t think he would like that,” she told me. “Not my fault,” she told Baba. “Your sister did it.”

I thought she was happy that my aunt’s work had been for nothing. I kept the dress on since it was the only nice garment I had, and walked back to the studio with my father, this time conscious of people’s looks and whispers, wondering if it was about me.

At the studio, I climbed on a high stool, crossed my ankles, and held the corners of the dress as I was told. The photographer’s greasy head disappeared underneath the black skirt of the camera. I looked at the glass lens in the darkness, trying to sit up straight.

No one said, “Smile!”

A few months later, as I was passing by the photographer’s studio, I saw my picture blown up to a poster size, hanged from a metal frame over the sidewalk for everyone to see. The black and white picture was retouched with shades of pink. There I was with my hair severely pulled back, zigzag bangs, where my aunt’s scissors had slipped, and a very serious look. I was proud of it every time I passed by. My father too enjoyed the picture, even though the photographer had not asked his permission to display it. I enclosed the picture with the first-grade application forms at age six.

Because Mehr-ayeen was a snobby school that rejected most Jewish kids, our family and friends tried to discourage my father from applying. Although it was a public school, the principal feared that its proximity to the mahaleh would entice too many Jews; and, if accepted, they would tarnish its image as an elite institution.

The day Baba took me for a first-grade interview felt like Rosh Hashanah. I watched my father shave the stubble on his face and the bushy hair under his armpits, wash his neck and behind his ears. He put a piece of cloth on the tip of a toothpick and scraped the wax from inside his ears. He dressed in his dark brown Shabbat suit and polished shoes. Then he brushed back his newly cut hair, and I thought he was the most handsome father.

My mother gave me a sponge bath in the yard and braided my hair tight in the back. She cut my nails and checked them for cleanliness and made sure I was wearing clean socks and underwear. I put on my fancy dress with a shawl for modesty.

My mother’s longing eyes followed us as we left without her. My father walked tall and erect. His mustache twitched as he bit his upper lip, trying to control his facial muscles that slipped into a smile.

I was torn between having to skip to keep up with his long strides or taking bigger steps.

“Act with modesty,” he scolded. “It’s improper to run like a farmer’s girl after chickens.”

I obeyed, taking little steps, but ran every few minutes to catch up. I was as excited as he was.

We crossed Lotf-ali-khan Street, a newly constructed street that ran like an arrow through the heart of the mahaleh, dividing it in half. The construction had been costly and labor intensive. Since the Jewish families refused to drink from the city water running through ditches, they each had a well in their homes. While destroying the Jewish houses to make room for the modern road, the engineers faced the nightmare of filling the sinking holes where the wells had existed for hundreds of years. This unexpected obstacle added to the cost of the construction immensely, infuriating the workers who thought it a Jewish sabotage. At the same time, the projec

t angered the homeowners, who were not adequately compensated. The Jewish community felt exposed and vulnerable as the ghetto was divided by a major thoroughfare, and was no longer within a common walled-in perimeter.

The new street, one of the very first paved roads in Shiraz, was jammed not only with cars and taxis but also with mules carrying food and spices and pedestrians trying to avoid bumping into each other. I could not possibly cross the chaotic street safely by myself.

My father and I finally approached the iron gates of the school. As we waited for permission from two gendarmes to enter and approach the office, I kept busy watching the activities in a small quilt workshop nearby. Two workers in loose pajamas bottoms and once-white undershirts rested their backs against the walls of the shop as they beat cotton, boing, boing, with a harp-shaped gadget. A cloud of cotton dust circulated in the dark shop as two other men on their hands and knees captured the cotton in a blue satin casing with large needles and rapidly quilted flowers and geometric designs onto its shimmering surface. I didn’t see the guards coming back to let us in.

My father grabbed my arms. “You’re covered in dust! Look at you!” He brushed my clothes with his handkerchief.

We went through the large doors. I stopped in the walled-in yard to look at the playground, the classrooms surrounding the courtyard, two stories of brick and glass. It was so big, so clean. We climbed the stairs to the office.

The principal was too busy to meet with us, a woman behind a small desk announced. She wore her hair in a low ponytail. The corner of her lips moved downward as if she had swallowed something rotten. She continued reading the stacks of paper on her desk without looking at us. I watched my father lose a few centimeters in height, but he did not acquiesce. He didn’t seem to be surprised at the unfriendly reception. This was a country of haggling and bargaining, in which my father was a master.

“Let me visit Mr. Principal, for just a few minutes,” he said with a bow and much humility. “I took the morning off, and the child’s heart will be broken. I beg respectfully.” He bowed again.

“Let’s go, Baba,” I begged. “I will go somewhere else. It’s okay.”

“Don’t act like a stupid donkey,” he whispered.

We waited by the door until the principal left his office. My father jumped, bowed in front of him again, and, holding his two hands together in respect, begged for a minute of his time.

The principal looked at us with a sigh of resignation. He was shorter than my father but looked tall. He pointed his finger at me. “She is too young.” He turned to leave.

My father followed him, waving my birth certificate. “But she is six years old. I was told by your secretary that she had to be six. She is six years old.”

“No room this year. We’re full. Why don’t you sign her up at the Jewish school? She’ll be more comfortable there with your own people.” He threw the words at us in a rapid blast uncharacteristic of proper Iranian behavior that demanded deliberate speech.

“No,” my father said. “We are closer to Mehr-ayeen, and this is where I want her to study.”

The principal stopped by the doorway, sighed again, and shook his head. He adjusted his tie and coat, looked straight at my father, and said, “Come back next year. We’re full for now.” He took a side glance at me and walked away.

My father didn’t pursue him. “His father is a dirty dog,” he spat. “A true Moslem would not do this, breaking the child’s heart.”

That was the last time I wore my nice dress. It was too fancy for everyday use; then I outgrew it.

The year I had to wait for my acceptance to the first grade was the longest year of my life. There was nothing fun to do. Paper and pencils were items of luxury, books nonexistent. I helped sweep the floors, clean the rice, wash the clothes, and all the other boring chores, which I hated and tried to escape as much as I could. That year, my lessons were of life, my teachers the people around me.

My mother was busy with my baby sister, whose severe infection kept her in the hospital more often than at home. Maman often sent me to my father’s shop to get me out of her hair. I loved going there to watch my father and uncle Morad thread little pearls on gold strings and sew them on wide bracelets in the shape of roses. I didn’t know then that their art would show up in museums during my adult life. I didn’t know that there would come a time when I longed for a small piece of the jewelry I watched my father create.

In the back workshop, I watched three young men, my father’s apprentices, polish silver platters and goblets for the customers. They enjoyed having me there, took turns putting me on their laps, spreading my skirt so it would not get mussed, holding me tight so I would not fall. Their hips moved up and down rhythmically.

My father disapproved of my wandering around the workshop, alone with young men. Many times, he took off his face shield, turned off his jeweler’s torch, shook the gold dust from his leather apron onto a metal container, and steaming, came to the back. Not being able to tell me of his fears (no one ever discussed such matters with children), he dragged me back to the main shop and ordered me to sit up straight, with my hands folded on my lap. Every time, after fifteen minutes, I became restless and jumped up and down, putting at risk large glass containers of acids used to purify the gold and the silver. Finally, my father forbade my mother to send me to his shop.

Soon I was looking for other means of entertainment. My father’s first cousin lived next door, and his daughter was my age. Mahvash was mischievous. Her carefree running around the streets of mahaleh with her skirt flying in the air appalled the neighbors. “Look at her running like a boy. The girl has no shame,” they would say, spitting on the ground with disgust.

My father forbade me to spend time with her after hearing the comments from our neighbors.

Years later, Mahvash would surprise all her classmates by participating in the competitions for Miss Iran. The self-confidence to think herself beautiful, deserving, to be adventurous and allow her pictures to appear in Zan-e Rouz, the premier women’s magazine, was beyond our imaginations. Many looked down at the way she exhibited herself, and wondered if she would ever find a husband. A Tehrani man saw Mahvash on television and fell in love with her. He found her address in Shiraz and asked for her hand from her parents.

Mahvash married at age fourteen. She looked like a dressed-up queen on her wedding night. She had a big smile, and when she saw me, she winked and pointed to her hair that was piled up on top. She pulled me to the side later. “Do you see the glitter on my hair?” she asked, a twinkle in her green eyes. “A special hairspray!”

Mahvash moved to Tehran and had three children by the time I graduated from high school. She was widowed by age thirty-five when her husband died of a heart attack. According to the Islamic laws reinstated by Khomeini, her father-in-law was in charge of the inheritance and the children’s welfare. Mahvash was lucky. Her father-in-law was a compassionate man who turned over the money to her and helped her and the children leave the country for the United States.

Mahvash and I found each other in Los Angeles when we were in our mid-forties. We had not seen each other for over twenty-five years. She was still beautiful—porcelain doll skin, green eyes, curvaceous body, the same mischievous half smile and twinkle in her eyes. In an outdoor café, I asked her how she remembered me as a child.

She lit a cigarette and blew the smoke away from me. “You went by the rules—too serious,” she said.

Her full lips parted in a seductive smile. She took another puff from her cigarette and laughed. She told me how she had tricked a bus driver, when she was eight years old, to take her and her cousins to downtown Tehran to visit her aunt.

“Please, sir, we lost our money and our aunt is waiting for us for lunch. She is probably worried to death!” They rode on top of the double-decker, singing from the top of their lungs.

I imagined her letting the wind blow through her blond hair, laughing with delight. I would never have dared. “Did you really do t

hat? Weren’t you afraid?” I asked her.

“See! You are still too serious. Who was going to get us?”

That was the difference between us as children. She looked at the world as if it were a playground. I envisioned a bogeyman around every bend.

“We were kids,” Mahvash added, smiling in her familiar playful way. “And guess what? After having lunch with my aunt, she gave us money for the bus home.” She took another puff from her cigarette and laughed. “I convinced everyone to buy ice cream, and once again we waited for the bus with no money. The same bus driver stopped and bought the story again, taking us home on his lunch break.”

Mahvash was right. I grew up to be suspicious of people. Like my father, I feared their judgment.

Originally, Mahvash jeered at me. My mother had my fine hair shaved when I was five years old. According to common beliefs, shaving made the hair grow thicker and more abundant. All winter, I went around wearing a kerchief so I would not catch a cold from my bald head. All winter, Mahvash made fun of my ugly scarf and hairless scalp. Later, when she began courting my friendship, I was both intimidated and intrigued.

She used to tell wild stories about how her brother ate a razor blade wrapped in a piece of bread to show how brave he was, and that her mother approved, saying it was nothing but pure iron that his body needed anyway. She told me that it was good to eat raw pistachios. I believed her despite hearing the opposite from my mother, who thought they would give me worms. She convinced me to go with her to the synagogue, put my head on its closed door, and ask God to take away the life of a neighborhood girl, who had angered her.

“Did you do it?” she asked.

I nodded.

“No, you say it aloud. I wanna hear it.”

I audibly cursed the girl, but silently asked God not to accept my words.

Mahvash and I roamed the narrow alleyways looking for something to do. She told me about a wonderful confectionery outside the mahaleh and about the unusual candies we could buy if we had money.

Wedding Song

Wedding Song